What Did Sophocles Experiences Outside the Arts Expose Him to

| Sophocles | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 497/496 BC Colonus, Attica |

| Died | 406/405 BC (anile 90–92) Athens |

| Occupation | Tragedian |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Notable works |

|

Sophocles (;[1] Ancient Greek: Σοφοκλῆς, pronounced [so.pʰo.klɛ̂ːs]; c. 497/half-dozen – winter 406/5 BC)[2] is one of three ancient Greek tragedians whose plays have survived. His kickoff plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those of Aeschylus; and earlier than, or gimmicky with, those of Euripides. Sophocles wrote over 120 plays,[iii] only only seven accept survived in a complete form: Ajax, Antigone, Women of Trachis, Oedipus Male monarch, Electra, Philoctetes and Oedipus at Colonus.[4] For well-nigh fifty years, Sophocles was the most celebrated playwright in the dramatic competitions of the city-land of Athens which took identify during the religious festivals of the Lenaea and the Dionysia. He competed in thirty competitions, won twenty-four, and was never judged lower than second place. Aeschylus won 13 competitions, and was sometimes defeated past Sophocles; Euripides won four.[5]

The most famous tragedies of Sophocles feature Oedipus and Antigone: they are generally known every bit the Theban plays, though each was part of a different tetralogy (the other members of which are now lost). Sophocles influenced the development of drama, most importantly by calculation a third actor (attributed to Sophocles by Aristotle; to Aeschylus by Themistius),[6] thereby reducing the importance of the chorus in the presentation of the plot.[ citation needed ] He also developed his characters to a greater extent than earlier playwrights.[seven]

Life [edit]

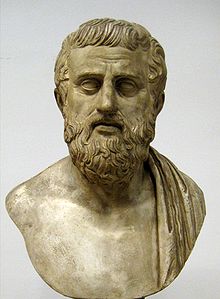

A marble relief of a poet, perhaps Sophocles

Sophocles, the son of Sophillus, was a wealthy member of the rural deme (pocket-sized community) of Hippeios Colonus in Attica, which was to get a setting for one of his plays; and he was probably born there,[2] [8] a few years before the Boxing of Marathon in 490 BC: the exact year is unclear, merely 497/half dozen is almost likely.[2] [9] He was born into a wealthy family unit (his begetter was an armour manufacturer), and was highly educated. His offset artistic triumph was in 468 BC, when he took first prize in the Dionysia, beating the reigning master of Athenian drama, Aeschylus.[2] [10] According to Plutarch, the victory came under unusual circumstances: instead of following the usual custom of choosing judges by lot, the archon asked Cimon, and the other strategoi present, to make up one's mind the victor of the contest. Plutarch farther contends that, following this loss, Aeschylus shortly left for Sicily.[xi] Though Plutarch says that this was Sophocles' first production, it is at present thought that his first product was probably in 470 BC.[eight] Triptolemus was probably one of the plays that Sophocles presented at this festival.[8]

In 480 BC Sophocles was chosen to atomic number 82 the paean (a choral chant to a god), celebrating the Greek victory over the Persians at the Boxing of Salamis.[12] Early in his career, the politician Cimon might have been 1 of his patrons; simply, if he was, there was no ill will borne by Pericles, Cimon'due south rival, when Cimon was ostracized in 461 BC.[2] In 443/2, Sophocles served equally one of the Hellenotamiai, or treasurers of Athena, helping to manage the finances of the urban center during the political ascendancy of Pericles.[2] In 441 BC, according to the Vita Sophoclis, he was elected one of the ten generals, executive officials at Athens, as a junior colleague of Pericles; and he served in the Athenian campaign against Samos. He was supposed to have been elected to this position as the result of his product of Antigone,[xiii] merely this is "most improbable".[14]

In 420 BC, he was chosen to receive the epitome of Asclepius in his ain house, when the cult was existence introduced to Athens, and lacked a proper place (τέμενος).[15] For this, he was given the posthumous epithet Dexion (receiver) by the Athenians.[16] Only "some incertitude attaches to this story".[15] He was also elected, in 411 BC, one of the commissioners (probouloi) who responded to the catastrophic devastation of the Athenian expeditionary force in Sicily during the Peloponnesian War.[17]

Sophocles died at the age of 90 or 91 in the winter of 406/5 BC, having seen, inside his lifetime, both the Greek triumph in the Western farsi Wars, and the bloodletting of the Peloponnesian War.[2] Equally with many famous men in classical antiquity, his death inspired a number of apocryphal stories. The most famous[ citation needed ] is the proposition that he died from the strain of trying to recite a long judgement from his Antigone without pausing to take a breath. Some other account suggests he high-strung while eating grapes at the Anthesteria festival in Athens. A 3rd holds that he died of happiness after winning his concluding victory at the Urban center Dionysia.[18] A few months subsequently, a comic poet, in a play titled The Muses, wrote this eulogy: "Blessed is Sophocles, who had a long life, was a man both happy and talented, and the writer of many proficient tragedies; and he ended his life well without suffering whatever misfortune."[xix] According to some accounts, however, his ain sons tried to have him declared incompetent about the end of his life; and that he refuted their charge in court by reading from his new Oedipus at Colonus.[xx] One of his sons, Iophon, and a grandson, called Sophocles, besides became playwrights.[21]

Homosexuality [edit]

An aboriginal source, Athenaeus'south work Sophists at Dinner, contains references to Sophocles' sexuality. In that work, a character named Myrtilus claims that Sophocles "was fractional to boys, in the same way that Euripides was partial to women"[22] [23] ("φιλομεῖραξ δὲ ἦν ὁ Σοφοκλῆς, ὡς Εὐριπίδης φιλογύνης"),[24] and relates an anecdote, attributed to Ion of Chios, of Sophocles flirting with a serving-boy at a symposium:

βούλει με ἡδέως πίνειν; [...] βραδέως τοίνυν καὶ πρόσφερέ μοι καὶ ἀπόφερε τὴν κύλικα.[24]

Do you desire me to savor my drink? [...] Then mitt me the cup prissy and slow, and take it back nice and irksome besides.[22]

He also says that Hieronymus of Rhodes, in his Historical Notes, claims that Sophocles once led a male child outside the city walls for sexual activity; and that the boy snatched Sophocles' cloak (χλανίς, khlanis), leaving his own kid-sized robe ("παιδικὸν ἱμάτιον") for Sophocles.[25] [26] Moreover, when Euripides heard about this (information technology was much discussed), he mocked the disdainful treatment, maxim that he had himself had sex with the boy, "but had not given him annihilation more than his usual fee"[27] ("ἀλλὰ μηδὲν προσθεῖναι"),[28] or, "but that aught had been taken off"[29] ("ἀλλὰ μηδὲν προεθῆναι").[thirty] In response, Sophocles equanimous this elegy:

Ἥλιος ἦν, οὐ παῖς, Εὐριπίδη, ὅς με χλιαίνων

γυμνὸν ἐποίησεν· σοὶ δὲ φιλοῦντι † ἑταίραν †

Βορρᾶς ὡμίλησε. σὺ δ᾿ οὐ σοφός, ὃς τὸν Ἔρωτα,

ἀλλοτρίαν σπείρων, λωποδύτην ἀπάγεις.[31]

It was the Dominicus, Euripides, and non a boy, that got me hot

and stripped me naked. Merely the Due north Wind was with you lot

when you were kissing † a courtesan †. You're non so clever, if you arrest

Eros for stealing dress while you're sowing some other man's field.[32]

Works and legacy [edit]

Portrait of the Greek actor Euiaon in Sophocles' Andromeda, c. 430 BC.

Sophocles is known for innovations in dramatic structure; deeper development of characters than earlier playwrights;[vii] and, if it was not Aeschylus, the improver of a third role player,[33] which further reduced the office of the chorus, and increased opportunities for evolution and conflict.[7] Aeschylus, who dominated Athenian playwriting during Sophocles' early career, adopted the third thespian into his ain work.[7] Besides the third actor, Aristotle credits Sophocles with the introduction of skenographia, or scenery-painting; merely this also is attributed elsewhere to someone else (by Vitruvius, to Agatharchus of Samos).[33] Subsequently Aeschylus died, in 456 BC, Sophocles became the pre-eminent playwright in Athens,[2] winning competitions at eighteen Dionysia, and half dozen Lenaia festivals.[2] His reputation was such that strange rulers invited him to nourish their courts; just, different Aeschylus, who died in Sicily, or Euripides, who spent time in Macedon, Sophocles never accepted any of these invitations.[2] Aristotle, in his Poetics (c. 335 BC), used Sophocles' Oedipus King as an example of the highest achievement in tragedy.[34]

But two of the seven surviving plays[35] can be dated securely: Philoctetes to 409 BC, and Oedipus at Colonus to 401 BC (staged later on his death, by his grandson). Of the others, Electra shows stylistic similarities to these two, suggesting that it was probably written in the later on part of his career; Ajax, Antigone, and The Trachiniae, are mostly idea early, again based on stylistic elements; and Oedipus Rex is put in a middle flow. Nearly of Sophocles' plays show an undercurrent of early fatalism, and the beginnings of Socratic logic as a mainstay for the long tradition of Greek tragedy.[36] [37]

Theban plays [edit]

The Theban plays comprise three plays: Oedipus King (also called Oedipus Tyrannus or Oedipus the King), Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone. All three concern the fate of Thebes during and after the reign of King Oedipus.[38] They have ofttimes been published under a single cover;[39] just Sophocles wrote them for separate festival competitions, many years apart. The Theban plays are non a proper trilogy (i.e. iii plays presented as a continuous narrative), nor an intentional series; they comprise inconsistencies.[38] Sophocles also wrote other plays pertaining to Thebes, such as the Epigoni, but merely fragments take survived.[40]

Subjects [edit]

The three plays involve the tale of Oedipus, who kills his father and marries his mother, not knowing they are his parents. His family unit is cursed for three generations.

In Oedipus Rex, Oedipus is the protagonist. His infanticide is planned past his parents, Laius and Jocasta, to prevent him fulfilling a prophecy; but the servant entrusted with the infanticide passes the infant on, through a serial of intermediaries, to a childless couple, who adopt him, not knowing his history. Oedipus eventually learns of the Delphic Oracle'south prophecy of him, that he would kill his father, and marry his mother; he attempts to flee his fate without harming those he knows every bit his parents (at this betoken, he does not know that he is adopted). Oedipus meets a man at a crossroads accompanied past servants; Oedipus and the man fight, and Oedipus kills the man (who was his father, Laius, although neither knew at the fourth dimension). He becomes the ruler of Thebes later solving the riddle of the Sphinx and in the process, marries the widowed queen, his mother Jocasta. Thus the stage is set for horror. When the truth comes out, following from another truthful only confusing prophecy from Delphi, Jocasta commits suicide, Oedipus blinds himself and leaves Thebes. At the end of the play, order is restored. This restoration is seen when Creon, brother of Jocasta, becomes king, and also when Oedipus, before going off to exile, asks Creon to have care of his children. Oedipus's children will e'er carry the weight of shame and humiliation because of their father's actions.[41]

In Oedipus at Colonus, the banished Oedipus and his girl Antigone get in at the boondocks of Colonus where they encounter Theseus, King of Athens. Oedipus dies and strife begins between his sons Polyneices and Eteocles. They fight, and simultaneously run each other through.

In Antigone, the protagonist is Oedipus' daughter, Antigone. She is faced with the choice of allowing her brother Polyneices' trunk to remain unburied, exterior the city walls, exposed to the ravages of wild fauna, or to bury him and face decease. The king of the land, Creon, has forbidden the burial of Polyneices for he was a traitor to the urban center. Antigone decides to bury his body and face the consequences of her actions. Creon sentences her to decease. Eventually, Creon is convinced to free Antigone from her punishment, but his decision comes also late and Antigone commits suicide. Her suicide triggers the suicide of two others close to Male monarch Creon: his son, Haemon, who was to wed Antigone, and his wife, Eurydice, who commits suicide later on losing her only surviving son.

Limerick and inconsistencies [edit]

The plays were written across thirty-six years of Sophocles' career and were not composed in chronological order, merely instead were written in the order Antigone, Oedipus Rex, and Oedipus at Colonus. Nor were they composed equally a trilogy – a grouping of plays to be performed together, but are the remaining parts of 3 different groups of plays. As a effect, there are some inconsistencies: notably, Creon is the undisputed rex at the stop of Oedipus Rex and, in consultation with Apollo, single-handedly makes the decision to expel Oedipus from Thebes. Creon is also instructed to look after Oedipus' daughters Antigone and Ismene at the terminate of Oedipus King. By contrast, in the other plays at that place is some struggle with Oedipus' sons Eteocles and Polynices in regard to the succession. In Oedipus at Colonus, Sophocles attempts to work these inconsistencies into a coherent whole: Ismene explains that, in light of their tainted family lineage, her brothers were at first willing to cede the throne to Creon. Even so, they somewhen decided to accept charge of the monarchy, with each blood brother disputing the other's correct to succeed. In addition to existence in a conspicuously more powerful position in Oedipus at Colonus, Eteocles and Polynices are too culpable: they consent (l. 429, Theodoridis, tr.) to their father'southward going to exile, which is i of his bitterest charges confronting them.[38]

Other plays [edit]

In addition to the three Theban plays, at that place are four surviving plays past Sophocles: Ajax, Women of Trachis, Electra, and Philoctetes, the last of which won first prize in 409 BC.[42]

Ajax focuses on the proud hero of the Trojan State of war, Telamonian Ajax, who is driven to treachery and somewhen suicide. Ajax becomes gravely upset when Achilles' armor is presented to Odysseus instead of himself. Despite their enmity toward him, Odysseus persuades the kings Menelaus and Agamemnon to grant Ajax a proper burial.

The Women of Trachis (named for the Trachinian women who make upward the chorus) dramatizes Deianeira's accidentally killing Heracles after he had completed his famous twelve labors. Tricked into thinking information technology is a love charm, Deianeira applies poison to an article of Heracles' wearable; this poisoned robe causes Heracles to die an excruciating death. Upon learning the truth, Deianeira commits suicide.

Electra corresponds roughly to the plot of Aeschylus' Libation Bearers. It details how Electra and Orestes avenge their male parent Agamemnon'southward murder past Clytemnestra and Aegisthus.

Philoctetes retells the story of Philoctetes, an archer who had been abandoned on Lemnos by the rest of the Greek armada while on the manner to Troy. Afterward learning that they cannot win the Trojan War without Philoctetes' bow, the Greeks send Odysseus and Neoptolemus to retrieve him; due to the Greeks' earlier treachery, withal, Philoctetes refuses to rejoin the regular army. It is only Heracles' deus ex machina appearance that persuades Philoctetes to go to Troy.

Fragmentary plays [edit]

Although over 120 titles of plays associated with Sophocles are known and presented below,[43] piddling is known of the precise dating of most of them. Philoctetes is known to have been written in 409 BC, and Oedipus at Colonus is known to have only been performed in 401 BC, posthumously, at the initiation of Sophocles' grandson. The convention on writing plays for the Greek festivals was to submit them in tetralogies of three tragedies forth with one satyr play. Along with the unknown dating of the vast majority of over 120 plays, it is too largely unknown how the plays were grouped. Information technology is, however, known that the iii plays referred to in the modern era every bit the "Theban plays" were never performed together in Sophocles' own lifetime, and are therefore not a trilogy (which they are sometimes erroneously seen as).

Fragments of Ichneutae (Tracking Satyrs) were discovered in Arab republic of egypt in 1907.[44] These amount to about one-half of the play, making it the all-time preserved satyr play after Euripides' Cyclops, which survives in its entirety.[44] Fragments of the Epigoni were discovered in Apr 2005 past classicists at Oxford University with the assist of infrared technology previously used for satellite imaging. The tragedy tells the story of the second siege of Thebes.[40] A number of other Sophoclean works have survived only in fragments, including:

Sophocles' view of his own piece of work [edit]

There is a passage of Plutarch'south tract De Profectibus in Virtute vii in which Sophocles discusses his own growth every bit a writer. A likely source of this material for Plutarch was the Epidemiae of Ion of Chios, a book that recorded many conversations of Sophocles; just a Hellenistic dialogue about tragedy, in which Sophocles appeared as a character, is likewise plausible.[45] The former is a probable candidate to accept contained Sophocles' soapbox on his own evolution considering Ion was a friend of Sophocles, and the volume is known to have been used by Plutarch.[46] Though some interpretations of Plutarch'southward words suggest that Sophocles says that he imitated Aeschylus, the translation does non fit grammatically, nor does the interpretation that Sophocles said that he was making fun of Aeschylus' works. C. M. Bowra argues for the following translation of the line: "After practising to the total the bigness of Aeschylus, then the painful ingenuity of my ain invention, at present in the third stage I am changing to the kind of wording which is well-nigh expressive of character and best."[47]

Here Sophocles says that he has completed a phase of Aeschylus' work, significant that he went through a phase of imitating Aeschylus' fashion but is finished with that. Sophocles' opinion of Aeschylus was mixed. He certainly respected him enough to imitate his work early on in his career, but he had reservations nearly Aeschylus' mode,[48] and thus did not keep his false upward. Sophocles' first stage, in which he imitated Aeschylus, is marked by "Aeschylean pomp in the language".[49] Sophocles' second stage was entirely his own. He introduced new means of evoking feeling out of an audience, as in his Ajax, when Ajax is mocked by Athene, so the stage is emptied so that he may commit suicide solitary.[50] Sophocles mentions a third stage, distinct from the other two, in his give-and-take of his development. The third stage pays more listen to diction. His characters spoke in a way that was more natural to them and more than expressive of their individual character feelings.[51]

Namesake [edit]

- Sophocles (crater), a crater on Mercury.

See also [edit]

- Theatre of ancient Hellenic republic

Notes [edit]

- ^ Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter, James Hartman and Jane Setter, eds. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th edition. Cambridge Upward, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f thou h i j Sommerstein (2002), p. 41.

- ^ The exact number is unknown, the Suda says he wrote 123, another ancient source says 130, but no verbal number "is possible", see Lloyd-Jones 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Suda (ed. Finkel et al.): s.5. Σοφοκλῆς .

- ^ Sophocles at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ LLoyd-Jones, H. (ed. and trans.) (1997). Introduction, in Sophocles I . Sophocles. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Printing. p. 9. ISBN9780674995574.

- ^ a b c d Freeman, p. 247.

- ^ a b c Sommerstein (2007), p. xi.

- ^ Lloyd-Jones 1994, p. vii.

- ^ Freeman, p. 246.

- ^ Life of Cimon 8. Plutarch is mistaken well-nigh Aeschylus' decease during this trip; he went on to produce dramas in Athens for another decade.

- ^ McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Earth Drama: An International Reference Work in 5 Volumes, Volume one, "Sophocles".

- ^ Beer 2004, p. 69.

- ^ Lloyd-Jones 1994, p. 12.

- ^ a b Lloyd-Jones 1994, p. 13.

- ^ Clinton, Kevin "The Epidauria and the Arrival of Asclepius in Athens", in Ancient Greek Cult Practice from the Epigraphical Evidence, edited by R. Hägg, Stockholm, 1994.

- ^ Lloyd-Jones 1994, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Schultz 1835, pp. 150–51.

- ^ Lucas 1964, p. 128.

- ^ Cicero recounts this story in his De Senectute seven.22.

- ^ Sommerstein (2002), pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Athenaeus (2011). The Learned Banqueters, Book 7. Douglas Olson, S. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. p. 53. ISBN9780674996731.

- ^ Athenaeus (1854). The Deipnosophists. Attalus.org. XIII. Translated by Yonge, Charles Knuckles. London: Henry G. Bohn. pp. 603–4. LCCN 2002554451. Retrieved 24 Apr 2021.

- ^ a b Athenaeus (2011). The Learned Banqueters, Volume VII. Douglas Olson, Due south. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. p. 52. ISBN9780674996731.

- ^ Athenaeus (2011). The Learned Banqueters, Volume Vii. Douglas Olson, Southward. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN9780674996731.

- ^ Fortenbaugh, William Wall. Lyco and Traos and Hieronymus of Rhodes: Text, Translation, and Discussion. Transaction Publishers (2004). ISBN 978-i-4128-2773-7. p. 161

- ^ Athenaeus (2011). The Learned Banqueters, Volume VII. Douglas Olson, South. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. p. 57. ISBN9780674996731.

- ^ Athenaeus (2011). The Learned Banqueters, Volume 7. Douglas Olson, Southward. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Printing. p. 56. ISBN9780674996731.

- ^ Sophocles (1992). Greek Lyric, Volume IV: Bacchylides, Corinna, and Others. Campbell, D. A. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Printing. p. 333. ISBN9780674995086.

- ^ Sophocles (1992). Greek Lyric, Book IV: Bacchylides, Corinna, and Others. Campbell, D. A. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard Academy Press. p. 332. ISBN9780674995086.

- ^ Athenaeus (2011). The Learned Banqueters, Volume Seven. Douglas Olson, Southward. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. p. 58. ISBN9780674996731.

- ^ Athenaeus (2011). The Learned Banqueters, Book VII. Douglas Olson, S. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. p. 59. ISBN9780674996731.

- ^ a b Lloyd-Jones 1994, p. nine.

- ^ Aristotle. Ars Poetica.

- ^ The first printed edition of the seven plays is by Aldus Manutius in Venice 1502: Sophoclis tragaediae [sic] septem cum commentariis. Despite the addition 'cum commentariis' in the title, the Aldine edition did non include the ancient scholia to Sophocles. These had to await until 1518 when Janus Lascaris brought out the relevant edition in Rome.

- ^ Lloyd-Jones 1994, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Scullion, pp. 85–86, rejects attempts to engagement Antigone to before long earlier 441/0 based on an anecdote that the play led to Sophocles' election as general. On other grounds, he cautiously suggests c. 450 BC.

- ^ a b c Sophocles, ed Grene and Lattimore, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Meet for example: "Sophocles: The Theban Plays", Penguin Books, 1947; Sophocles I: Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone, University of Chicago, 1991; Sophocles: The Theban Plays: Antigone/Male monarch Oidipous/Oidipous at Colonus, Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company, 2002; Sophocles, The Oedipus Cycle: Oedipus Rex, Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone, Harvest Books, 2002; Sophocles, Works, Loeb Classical Library, Vol I. London, W. Heinemann; New York, Macmillan, 1912 (oftentimes reprinted) – the 1994 Loeb, however, prints Sophocles in chronological club.

- ^ a b Murray, Matthew, "Newly Readable Oxyrhynchus Papyri Reveal Works past Sophocles, Lucian, and Others Archived eleven April 2006 at the Wayback Machine", Theatermania, 18 April 2005. Retrieved ix July 2007.

- ^ Sophocles. Oedipus the King. The Norton Anthology of Western Literature. Gen. ed. Peter Simon. 8th ed. Vol. 1. New York: Norton, 1984. 648–52. Print. ISBN 0-393-92572-2

- ^ Freeman, pp. 247–48.

- ^ Lloyd-Jones 2003, pp. 3–ix.

- ^ a b Seaford, p. 1361.

- ^ Sophocles (1997). Sophocles I. Lloyd-Jones, H. (ed. and trans.). Cambridge, MA; London, England: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Printing. p. eleven. ISBN9780674995574.

- ^ Bowra, p. 386.

- ^ Bowra, p. 401.

- ^ Bowra, p. 389.

- ^ Bowra, p. 392.

- ^ Bowra, p. 396.

- ^ Bowra, pp. 385–401.

References [edit]

- Beer, Josh (2004). Sophocles and the Tragedy of Athenian Commonwealth. Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0-313-28946-8

- Bowra, C.Thou. (1940). "Sophocles on His Own Development". American Journal of Philology. 61 (4): 385–401. doi:x.2307/291377. JSTOR 291377.

- Finkel, Raphael. "Adler number: sigma,815". Suda on Line: Byzantine Lexicography . Retrieved xiv March 2007.

- Freeman, Charles. (1999). The Greek Accomplishment: The Foundation of the Western World. New York: Viking Printing. ISBN 0-670-88515-0

- Hubbard, Thomas K. (2003). Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Bones Documents.

- Johnson, Marguerite & Terry Ryan (2005). Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature: A Sourcebook. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17331-0, 978-0-415-17331-5

- Lloyd-Jones, Hugh & Wilson, Nigel Guy (ed.) (1990). Sophoclis: Fabulae. Oxford Classical Texts.

- Lloyd-Jones, Hugh (ed.) (1994). Sophocles: Ajax. Electra. Oedipus Tyrannus. Edited and translated by Hugh Lloyd-Jones, Loeb Classical Library No. 20.

- Lloyd-Jones, Hugh (ed.) (1994). Sophocles: Antigone. The Women of Trachis. Philoctetes. Oedipus at Colonus. Edited and translated by Hugh Lloyd-Jones, Loeb Classical Library No. 21.

- Lloyd-Jones, Hugh (ed.) (1996). Sophocles: Fragments. Edited and translated by Hugh Lloyd-Jones, Loeb Classical Library No. 483.

- Lucas, Donald William (1964). The Greek Tragic Poets. West.Westward. Norton & Co.

- Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vols. five & 6 translated by Paul Shorey. Cambridge, MA, Harvard Academy Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1969.

- Schultz, Ferdinand (1835). De vita Sophoclis poetae commentatio. Phil. Diss., Berlin.

- Scullion, Scott (2002). Tragic dates, Classical Quarterly, new sequence 52, pp. 81–101.

- Seaford, Richard A. S. (2003). "Satyric drama". In Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth (ed.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (revised 3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1361. ISBN978-0-19-860641-iii.

- Smith, Philip (1867). "Sophocles". In William Smith (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. iii. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. pp. 865–73. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- Sommerstein, Alan Herbert (2002). Greek Drama and Dramatists. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26027-2

- Sommerstein, Alan Herbert (2007). "General Introduction" pp. eleven–xxix in Sommerstein, A.H., Fitzpatrick, D. and Tallboy, T. Sophocles: Selected Fragmentary Plays: Volume ane. Aris and Phillips. ISBN 0-85668-766-9

- Sophocles. Sophocles I: Oedipus the Male monarch, Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone. 2nd ed. Grene, David and Lattimore, Richard, eds. Chicago: Academy of Chicago, 1991.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. "Macropaedia Knowledge In Depth." The New Encyclopædia Britannica Volume xx. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2005. 344–46.

External links [edit]

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sophocles |

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sophocles. |

- Works past Sophocles at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Sophocles at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Sophocles at Internet Archive

- Works past Sophocles at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Sophocles at the Perseus Digital Library (Greek and English)

- SORGLL: Sophocles, Electra 1126–1170; read past Rachel Kitzinger

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophocles

0 Response to "What Did Sophocles Experiences Outside the Arts Expose Him to"

Post a Comment